In Bruges

By Ernest Mathijs

A slow burner about burning in hell, In Bruges was initially neither an impressive release nor a catastrophic failure.

A slow burner about burning in hell, In Bruges was initially neither an impressive release nor a catastrophic failure. Some commentators were quick to proclaim it a cult film (one of them was Chuck Palahniuk, writer of Fight Club), but most of its reputation grew gradually. In the years since its premiere at the Sundance festival in January 2008, it has slowly, and mostly through word-of-mouth, slipped into cult status. It now has a firm following of devoted fans who cherish the highly quotable back-and-forth dialogue, the swirling comedy-of-errors plot and its many maze-like inferences, the dark, existential humour, and the volatile mix of tragedy, sadness, principled moral stands and nihilism.

The key to In Bruges is its nothingness. Nothing works, nothing is sacred; every action misses its goal; everyone is misunderstood; and no one escapes. The main story is that of two London-based Irish hit-men who hide out in the picturesque medieval town of Bruges because of some messed up business back home. Ken (Brendan Gleeson) is the veteran of the two, and he enjoys the sense of eternity the city exudes. Ray (Colin Farrell) does not: acting like a pouting six-year old, he whines wherever they go, ridiculing the religious relics they visit – he is particularly unimpressed with the Chapel of the Holy Blood. The only brief reliefs for his mood are beers (not “gay beers” as he calls the Belgian ales, but “normal beers,” like lager) and impromptu encounters with a racist dwarf actor (Jordan Prentice) and the angelic film-set assistant Chloe (Clémence Poésy, Fleur from the Harry Potter films). The film reveals Ray’s moodiness to be the result of guilt – he accidentally shot a child once. For his involvement in that killing Ray’s strangely principled boss Harry (Ralph Fiennes) has ordered his elimination, by Ken. But like all other plans in the film, that arrangement fails and everything falls apart in Last Judgment-fashion amidst the fairytale beauty and moral solemnity of the Christmastime city, which becomes their prison – a confirmation of Bruges’ function as heaven, purgatory and hell, and a wink to the city’s medieval heritage which the film had portrayed so ominously in the film. In the last scene, Ray prays for redemption and slips into blissful nothingness. The grave symbolism of this sad story is redirected through some of the most remarkable dialogue of recent decades – smart and witty yet also blunt and offensive (and overloaded with ‘f-bombs’) – and through several clever allusions, to medieval allegory and to film history. The meeting with Chloe on a film set is one example. It is “a Dutch movie,” Chloe explains, “a dream sequence. It’s a pastiche of Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. Not a pastiche but a… ‘homage’ is too strong… A ‘nod of the head’.” The film-in-the-film itself looks like a painting by Hieronymus Bosch (which Ray and Ken actually visit earlier in the film). Such elaborate allusions are plentiful in In Bruges and they produce an alternative, cultist way of seeing the film that fans worldwide latched onto.

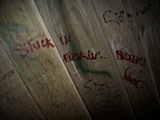

Director Martin McDonagh, known primarily for his savage, Tarantinesque theatre plays of revenge and violence set in rural Western Ireland, already had somewhat of an offbeat reputation when In Bruges was released – mostly thanks to his short Six Shooter, a hyperbolic homage to Spaghetti Westerns that features the explosion of a cow and the execution of a rabbit. In our poll that searched for the ‘newest cult film’ In Bruges was the single most mentioned title when the count closed, on June 1st 2011. It is a fan favourite by a small but telling margin. It far outruns any other films as a second and third choice, and it appears as a point of reference for cultism today in several comments to other films. It has its opponents, and its supporters are loud too – the number of exclamations and expletives suggest its fans share some of Ray’s vocabulary. Throughout, there is also a sense that, like it or not, the film has earned its place amongst canonical cults. Even Bruges’ own heritage now bears the marks of In Bruges’ cult status – the Belfry Tower in and around which much of the film is set is now tagged with graffiti quotations from the film, Amongst the most prominent are the phrases “Bruges is a shithole” and the politically highly incorrect yet apt summary of the film: “they’re filming midgets!” The writing is literally on the wall, then: In Bruges has enshrined itself into the history of churches and cults.

You Called it Cult: In Bruges Is the Latest, Newest Cult Film

By Babak Tabarraee

When the count stopped, on June 1st 2011, In Bruges was mentioned 95 times out of a total of 282 answers as the film most likely to become the newest, latest cult film.

When the count stopped, on June 1st 2011, In Bruges was mentioned 95 times out of a total of 282 answers as the film most likely to become the newest, latest cult film. Of all 25 candidates, films from the last six years, it garnered the most votes.

Martin McDonagh’s multi-national film was the first choice of 40 respondents, the second choice of 24, and the third choice of another 24. Seven of them found it the least likely option to become a cult film in the future.

Many of the respondents who voted for In Bruges did not even explain the reasons for their choices; they left a blank space which could be read as the obviousness of their choices to them, among many other possibilities. But there are also quite a few explanations, and these can be classified into seven categories, in order of significance:

1) Formal Readings and Aesthetic Qualities:

The largest group of comments consists of remarks on the film’s qualities. This ranged from vague descriptions such as “a good movie” to specific displays of admiration for the performances of the actors, storytelling, characterizations and the content. Occasionally, a more intertextual remark such as “[the film] adds a few nice tweaks and original ideas to the gangster genre” would be linked to the aesthetic quality of the film. The ultimate point of reference seems to be Quentin Tarantino, especially Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. Surrealism too appears regularly.

2) Reception and Fan Talk:

Equally often, respondents commented on In Bruges’ public presence. The scale of the film’s release, both its mainstream attraction and niche reception, the enthusiastic fan-talk and debates about it, and predictions of its long-lasting impact, “for macabre fan-boys” and “small, cinephile circles” alike, are listed as often as the formal readings as part of the cult-potential of In Bruges.

3) Mood, Atmosphere, Tone, and Look:

Several respondents felt the tone and mood were noteworthy, whether derived from the structure of the film or from the audience’s interpretations. According to these comments, the “dark, funny, violent, and indescribable tone” of In Bruges attests to the importance of tonality in recognizing cultishness. Withnail and I is a noted point of reference.

4) Personal/General Tags

Quite frequently, comments would consist of a mix of personal emotive vernacular and cultural slang. We have called these phrases ‘tags’: markers of appreciation associated with movies that have found a personal articulation. For In Bruges, “cool”, “awesome”, “shit”, “favourite”, “best”, and “enjoyable” were some of the adjectives used to describe a film that “pushes the right buttons.”

5) Quotability:

Along the same lines, but more specific, several comments remarked on the quotability of the idiosyncratic script of McDonagh (calling it “infinitely quotable”), and mentioned memorable lines of the film, describing them as “dark, unpredictable, sick and funny”. The vocabulary of In Bruges is an important specific reason for its cultish appeal.

6) Repeat-Viewing:

A characteristic of cult and fan receptions, the repeat-viewing of In Bruges is mentioned explicitly on five occasions and alluded to on several others. One interesting point is that in many of these cases, respondents do not so much make a general comment on repeat-viewing but rather emphasize their own, personal experience of re-watching the film. It gives this category a decidedly personal touch.

7) Pedigree:

And then there is knowledge of the careers of cast and crew prior to In Bruges. A few comments referred to the cultish fame of McDonagh as a playwright. In addition, one person stresses that, “Colin Farrell finally gives a great performance we all know was in him.” It’s a detail, perhaps, but one that matters. Remarkable is also that not a single comment makes mention of Harry Potter’s Clémence Poésy.