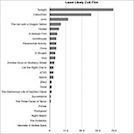

Our survey asked which film you felt was least likely to become a cult film anytime soon. To the left is a chart with the full results. It is doubtful that the top-two positions will surprise anyone. There are few films as passionately hated as Twilight and Catwoman. Yet, are films so vehemently despised and ridiculed as Twilight and Catwoman not also a challenge to public tastes, and therefore an example of paracinema par excellence? Isn’t there something sinister in denying female fandom the kind of agency male fandom of rape-revenge films is accorded? Isn’t that also a reason why we find The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo high on this list: bad because it is a challenge to normative values? Opinions differ, of course, but further on this page are three essays that ask if (just if) the badge of badness is not also one of honour.

For an essay on Juno please see our Stats and Surprises Page.

Twilight

By Lisa Bode

For many traditional cult media fans, the suggestion that Twilight (2008) is a cult film might be considered laughable. For, although initially produced on a fairly modest budget, Catherine Hardwicke’s adaptation of the first of Stephenie Meyer’s teen vampire romance novels has become part of a mammoth blockbuster franchise. Its vampires offend horror film lovers by sparkling in sunlight like anaemic disco-balls; hundreds of column inches have been devoted to skewering its dubious sexual politics; and its audience is narrowly painted as naïve tween/teen girls who will eventually outgrow it. But Twilight’s fandom is actually diverse and highly active. They are marked off from mainstream casual viewers with a somewhat derisory label that evokes their intense adoration – ‘Twihards’ – and their devotion takes different forms: repeated, ritual, celebratory and ironic viewing; and a proliferation of creative responses such as cartoons, video parodies, commentaries and re-edits. Indeed, Twilight, more so than its glossy sequels, appears to lend itself to a greater variety of these fan activities. Why? The deliriously swoony girl-meets-mysterious-boy storyline, underpinned by blue-hued lingering close-ups of beautiful faces gazing at each other, melancholic pop, a seductive fantasy universe, and sustained sexual tension can trigger a dopamine hit, lending it a compulsive rewatchability. At the same time, glittery vampires, clunky dialogue (“you better hold on tight, spidermonkey!”), cardboard cut-out characters, amateurish special effects and Robert Pattinson’s often comically intense performance of vampire celibacy are the source of the film’s ironic pleasures (or displeasures). Moreover, swooning and irony are not necessarily mutually exclusive responses, as indicated by the popularity of things like the Rifftrax DVD commentary among Twilight’s fan communities. Will this cult last? Hard to say, but it is likely that as years pass, fans’ intense devotion will give way more to camp irony and affectionate nostalgia.

Catwoman

By Ernest Mathijs

Poor Catwoman. It is the least liked film in our survey, by a mile.

Poor Catwoman. It is the least liked film in our survey, by a mile. Strictly speaking, Twilight received more disapproval, but it also got more ‘yes’ votes. Catwoman is the only film of the twenty-five we suggested that was never, ever, selected as a probable cult film. Not even mentioned once as a third choice. And the comments explaining why Catwoman is the film least likely to become cult appear to feel it’s self-evident why: “seriously” says one dry comment; “er… it’s CATWOMAN!!!” explains a slightly more elaborative observation. Me-ow indeed.

For camp value, a cat-like female superhero on killer heels wearing ripped and revealing clothing should be at least as good as a wet-shirted Colin Firth, or Christopher Reeves in red underwear. Speaking of those heels, why do so many dislikers single them out as “improbable?” Is donning a long red cape more practical attire for fighting crime? Didn’t think so. But alas, no comparisons seem to help. If Hale Berry’s shout-out at the Razzie awards for worst film of the year, and her subsequent paracinematic slumming in all kinds of worrisome films, cannot turn Catwoman into a cult, then nothing can. And if a cameo by Sharon Stone, a French cartoon director, and a comic-book pedigree make no difference, nothing will. Nor is Catwoman thrown the buoy that saved Plan 9 From Outer Space and The Room: the so-bad-it’s-good logic does not seem to apply to a film in which female protagonists are hyperbolically bad. Only men can be ‘so-bad-it’s-good.’ Women are just bad.

No film can be willed into cult status. That is not so hard to accept. But isn’t there something sinister about the disapproval Catwoman receives, if one takes into account that all this hate is directed to an African-american female superhero? Heck, cultists accepted even Arnold Schwarzenegger. It might be a coincidence. Maybe Catwoman is just beyond cult, too far ahead of its time to be bent into taste hierarchies. Take that, Pierre Bourdieu.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

By Russ Hunter

Adapted from the first of Stieg Larsson’s popular Millennium book series, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo follows hard-hitting and controversial political journalist Mikael Blomkvist as he is hired by wealthy businessman Henrik Vanger to discover what happened to his niece, who mysteriously disappeared years before. Yet the real mystery at the heart of the film is embodied in the character of Lisbeth Salander, the chameleon-like hacker extraordinaire who helps to recruit Blomkvist and then later becomes his lover and guardian angel. Like the Larsson novel upon which it is based, The Girl With the Dragon attempts to expose the injustices of Sweden’s so-called perfect socialist state, picking away at what the film suggests are seldom-uncovered lies, conspiracies and moral wrongs.

What makes The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo stand out as a cultish property is the double enigma at the heart of its narrative. Not only is the plot fundamentally about the search for a missing girl, but Salander herself is an enigma, her back-story slowly pieced together but never completely resolved as the film progresses. As part victim, part avenging angel, Salander is a contradictory, complex and an altogether delphian creation. Her brooding neo-punk look, diffident manner and sexual proclivities all suggest a figure that is not only at the margins of society but one that is actively threatening it. Lisbeth both looks like a threat and acts in a way that suggests she could threaten the seemingly ordered fabric of society if she wanted to. She can get in anywhere, be anyone and find out anything. But Salander is more than a cipher for an alternative subculture and an alternative Sweden. She both fights the system and ultimately acts a corrective to it. She has no boundaries in her search for vengeance, meting out justice where the legal system can’t or won’t.

Salander bears an interesting comparison with Diabolik, the anti-hero of Mario Bava’s 1968 film Danger: Diabolik. Like Lisbeth, Diabolik has a shape shifter’s ability to become anyone and gain entry anywhere. But Salander’s acts are rarely done for financial gain: she is a liberator, not a collector of things. Her heighted hacking and subterfuge skills give her an apparent omnipresence, even when she is off-screen for large sections of the film. Crucially, she is not constrained by patriarchal institutions; it is she who has the power to liberate, first herself and then eventually Blomkvist.

Liberated Lisbeth: the avenger of greed? (fan wallpaper)

Liberated Lisbeth: the avenger of greed? (fan wallpaper)